A man makes his way through Manhattan’s busy streets near Union Square Park swinging a plastic bag filled with egg shells, wilted greens and coffee grounds by his side.

As the day progresses, many follow suit, carrying food scraps in metal tins, old ice-cream containers and soggy paper bags. In turn, they each deposit their collections into large, plastic drums on the northwest corner of the park.

These New Yorkers are taking part in the city’s food scrap drop-off program, a collaboration between the New York Department of Sanitation (DSNY) and a number of environmental groups helping to reduce food waste across communities. Prianka Srinivasan reports.

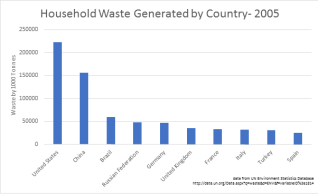

Managing waste in urban centers like New York has become a major global concern, with food waste set to increase by 44 percent worldwide in 2025 from 2005 levels, according to studies by McGill University in Montreal.

The environmental impact of this uneaten food is immense. Emitting 3.3 Giga tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere, decomposing waste produces almost as much greenhouse gas as do China and the US, and it occupies a staggering 1.4 billion hectares of land, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Community compost projects like the one in New York are a way for individuals to take a small bite out of this vast environmental problem—and the idea is catching on. Small-scale initiatives to reduce food waste have been trailed in cities as widespread as Kerala, India; Stockholm, Sweden; Adelaide, Australia, and, of course, New York.

The Compost Project in New York, operating since 1993, functions as a way for city dwellers to participate in the disposal and recycling of their waste. Every week, residents collect unused organic scraps from their homes (discarded carrot tops, banana peels and half-eaten meals all qualify) and, in a sort of odd ritual, descend upon the 71 drop-off sites scattered across the city. After residents empty their containers, the resulting piles of malodorous garbage—the layers at various stages of rot—are transported to one of several New York facilities to be composted.

Completely funded by New York City Department of Sanitation, the project relies on partnerships with seven local organizations to draw in community members and provide the knowledge and resources needed to compost their waste. Marguerite Manela, program manager of the NYC Compost Project at the DSNY, says community networks have been integral to ensuring the project’s longevity.

“We need to constantly engage people wherever they are,” Manela said. “Working from the ground up builds support for composting through these partnerships.”

With the recent announcement of New York’s Zero Waste initiative, the city has pledged to eliminate all waste sent to landfill by 2030. Residential composting has formed a fundamental part of this plan, and the city is currently piloting a curbside compost collection project, where residents in target neighbourhoods can dispose of their food waste in bins outside their homes.

It has nevertheless been a tough sell. Organic material still makes up 30 percent of all residential waste sent to landfill in New York, according to DSNY figures, and many residents participating in the curbside collection project have complained of the stench and rodents the decomposing waste attracts. Numerous recent reports also have labelled legislative shortcomings as the true culprit of the urban waste problem. In a 2011 study titled “Blaming the Consumer” David Evans, senior fellow at the Sustainable Consumption Institutes, argues that it is the “social and material conditions in which food is provisioned,” and not individual inaction, that lead to high levels of urban food waste.

Put another way, if legislators do not step in, individuals are left with the Sisyphean task of trying to roll their garbage up a steep hill. Someone is bound to get dirty.

Ashley Rafalow from the New York City Food Policy Center agrees. Though the responsibility to better manage food waste is shared between government and individuals, Rafalow sees government as having a fundamental role in making composting accessible to residents. For Rafalow, participation in the Compost Project is often reduced to “a labor of love” on the part of individuals, and the time and energy needed to collect food scraps and deposit them at composting stations can be a burden on many residents. This is where government policy is needed to provide incentives and facilitate composting to ensure that the management of food waste is not simply left to those with the privilege of time or resources, says Rafalow.

Big Reuse is a not-for-profit organization partnered with DSNY’s Compost Project, and recycles not only food waste but other residential waste as well. Alongside its composting facility in the neighbourhood of Astoria is BIG Reuse’s large warehouse which sells used furniture at heavily discounted prices. Steve Haskins, BIG Reuse’s director of operations, is often shocked at the quality and value of items donated to the store, which otherwise may have ended up in landfill.

“The problem is people have too much money,” says Haskins. He believes that this affluence drives a materialistic culture where people throw away unused items and food without thinking of the larger environmental effects.

If this is the case, recycling and composting is one way that individuals can mitigate the negative impact of their waste. Queens Botanical Gardens, another community partner of the Compost Project, uses the compost produced from its residential waste collection to grow vegetables in its urban farm. The vegetables are then donated to City Harvest, which uses them to help feed some of New York’s most vulnerable residents.

It is not just social imbalances that can be redressed through composting. Jeremy Teperman, project coordinator of the NYC Compost Project hosted by Queens Botanical Garden, sees composting as a way for city dwellers to get back in touch with natural food systems, which have been so skewed by modern lifestyles.

“I think that composting is ingrained in us,” Teperman said. “This is a system nature has derived to recycle waste… through composting, humans have found a way to mimic nature.”

The composting site at Queens Botanical gardens processes approximately 1,000 pounds of residential food waste a week collected from various drop-off sites. The waste is initially left to decompose in aerated beds for three weeks, where temperatures can reach upwards of 170 degrees Fahrenheit. The resulting black matter is then mixed with dried leaves, woodchips and other carboniferous material and left to stew for another three to four weeks. Once the soil is ready, and the waste completely decomposed, the compost can then be used throughout the gardens to nourish its plants.

Teperman sees individuals in cities such as New York as being increasingly distanced from this natural food system. The cultivation, consumption, disposal and regeneration of food are no longer integrated into urban lifestyles in a visible way. Community composting projects attempt to reintroduce people to this cycle, and, for Teperman, this is where waste reduction initiatives are most powerful—not as grand government schemes, but as sites where people can learn about the environment in a personal way.

“A lot of what we do is giving people knowledge and inspiring people to see the bigger picture,” Teperman said. “We want to involve people in the process.”

The goal of the Compost Project is not necessarily for individuals to completely eliminate waste, but rather for them to understand how their waste affects the larger ecosystem. Manela from DSNY agrees, saying that “the goal is to turn around thinking and start a conversation…something that might be disgusting can turn into something beautiful.”

This article has been revised to correct the name of the Union Square activity to “food scrap drop-off program,” to correct that it is financed completely by the New York City Department of Sanitation, not the City Council, to correct that the site of the photos is Grand Army Plaza, not Union Square, and to clarify Ashley Rafalow’s views.